“Only the Sith deal in absolutes.”

I know, I know. A hokey Star Wars reference. [Sorry, new Episode 7 trailer on the brain]. But in this, I have to agree with the Jedi. More often than not, dealing in absolutes is not a good thing.

But when it comes to the subject of bricks, people tend to fall hard one way or the other on the subject.

Generally speaking, we’re not fans of assigning bricks to our athletes for a number of reasons, which I’ll detail below. When we do, it’s for a specific purpose, which I’ll also explain.

But I want to address two points right up front, because this is a long-ish article and I don’t want you to miss these.

- You can effectively train for triathlons, successfully compete in triathlons, call yourself a triathlete, and not do bricks.

- You will hear many triathletes say they are running better or faster than ever because they are doing bricks. However, it is far more likely they are achieving better run results because they are running more. The fact that part of their run volume comes after a bike ride is, for the most part, irrelevant. Ultimately, it comes down to run volume and the intensity of those runs.

So back to our athletes. When they discover that their training programs are mostly brick-free—especially our long-course athletes—we’re asked, “Why? Why no bricks? I am a triathlete, therefore, I must do bricks.”

This is an absolute if you’re a triathlete, right?

Sort of like, “I am a triathlete, therefore, I must ride a tri bike.” [Author shakes head. No, this would require another blog article entirely].

But—and maybe I should have included this in the bulleted items above—there is no journal published study that says if you do bricks, you will go faster. If it’s out there, please let me know, because I would be extremely interested in reading it. In the meantime, any “evidence” that might exist to support this claim is purely anecdotal.

Well, shoot, I wanted to stick with a Star Wars theme, but the Black Knight with “dead” legs seemed a tamer image than Anakin Skywalker without legs.

The Early Days

In the early days of triathlon, we thought “dead” running legs following the bike were a result of poor training methods. Therefore, we reasoned, our training methods needed to change to more specifically replicate what we were experiencing in a race environment.

That is, we needed to practice running after biking. So, we all did bricks.

How the word brick came to be used in triathlon parlance is debatable. It’s largely accepted that the term came about because our legs tend to feel like bricks when we get off the bike. A story also exists of a duathlete who invented the name, one whose last name was Brick. Or perhaps, it’s that you’re stacking two workouts on top of each other, like a pile of bricks. Regardless, when we talk about brick workouts, we’re referring to running after biking.

What’s really happening in the transition from bike to run?

Since those early days, we’ve come to know that there are two physiological reasons for that “dead-leg” feeling from bike to run—blood shunting and neural transition.

- Blood shunting. When cycling, blood is directed to the major working muscles required for cycling, the quadriceps. Your blood vessels dilate and the flow of blood increases. This widening of the blood vessels is called vasodilation. So, stated basically, when you jump off your bike, you’ve got a lot of blood “pooled” in your quads. This is the heavy feeling. The blood then has to shunt to the major working muscles used for running, which are the hamstrings and the calves.

- The neural component. The nervous system is actively engaged in making biking movements—spinning, pedaling—and then, in T2, you’re asking your body to do something different and do it quickly—that is, make movements required for running, which involves impact and supporting your body weight.

It is important to note that regardless of how you train, the blood shunting has to happen and the nervous system has to adjust to new movements. The time required for these adjustments varies.

It is generally accepted that it takes about four to eight minutes for the blood shunting to occur. For some athletes, it may be less, for others, it may be more.

On the neural side, we’re talking less time than blood shunting, and your body can train to learn this “skill,” to move more rapidly from the neural patterning required for biking to that required for running. This is where shorter bike-run repeats come in and this might be applicable for certain short-course athletes.

However, it is unclear whether doing bricks allows blood shunting to occur more rapidly. Again, if there’s a journal-published study out there that shows this conclusively, we haven’t seen it.

But whether or not brick workouts speed the shunting process, you’re going to have this transitional period in any triathlon run, where you might feel a little lethargic, slow, and heavy.

I have a list below of circumstances when bricks might be warranted, and I’ve just mentioned one of those occasions above. But this is a good place to mention another one. If you’re newer to the sport and haven’t raced enough to have gotten used to the feeling of transitioning from bike to run, a short run after a bike might be ok. The good news is the more you race, the more your brain becomes accustomed to the sensation, and eventually, you stop noticing it altogether.

Bricks for the long-course athlete

“I did a seven-hour bike and then a three-hour run. I killed it.”

You hear this all the time, right? Think back to your last track workout with your tri club. Your last group ride. Your last Masters swim workout. There’s always that guy or gal that brags about their all-day-long brick. And, oh by the way, they do that every weekend. “So what are you doing?” they ask.

But think about it. Should long-course athletes really be practicing running after a long bike? This is a popular notion, however . . .

. . . the theoretical purpose of a brick is to train your body to run quickly—immediately—after the bike.

Hmm . . .

In an iron-distance race, you have 26.2 miles to “find” your legs. Even if you could train to speed the blood shunting process, how much would you gain by running the first 800 meters of an Ironman marathon quickly? Or think of it this way. Has any Ironman finisher ever lamented they ran the first mile of their marathon too slow?

What is really gained during a brick workout?

Since the blood shunting and neural transition take “x” amount of time, then what, specifically, is an athlete accomplishing during that “x” amount of time when running immediately following a bike workout?

Training the body’s mechanisms to reduce the amount of time it takes to shunt the blood?

Perhaps.

Training the body’s nervous system to affect a more rapid change in neural pattering from bike to run?

Probably.

Getting used to the feeling of running while the blood is shunting ?

Again, probably.

So answer me this:

What are athletes accomplishing after that “x” amount of time, when the blood shunting and neural transition are complete?

When it comes down to it, they’re completing a run workout at that point—a run workout like any other, one that could have been done before the bike, later in the day, or the next day.

“But, I need to learn to run on tired legs!”

Often, this is the justification for doing long bricks.

So what is tired?

- The accumulation of too much lactic acid. You would feel this type of fatigue at the end of a 5K running race, for example.

- Problems with nutrition. When you don’t hit the nutrition numbers right, you can deplete your glycogen stores and bonk. Or, you may have tried to throw down too many calories. Or, you may be working at too high an intensity, which affects caloric absorption rates. Or, your fluid replacement numbers might be off—too little or too much. Or, you may have an electrolyte imbalance—too little salt.

- Overheating. This is what you feel in the last two hours of your long ride in the middle of July in Arizona—slow, sluggish, just get me off this *@$! bike.

- Loss of muscle contractility. This is fatigue due to microscopic tearing of the muscles due to impact forces and is typically the type of fatigue felt at the end of a marathon. Without going into huge detail about eccentric muscle contractions and the stress put on muscles when running, think non-weight bearing exercise (cycling) versus weight-bearing (running). You’re going to be more beat up after a run than a ride.

After a low intensity, long bike ride, accumulation of too much lactic acid is not going to be an issue, nor is loss of muscle contractility, because of the non-weight bearing nature of cycling.

So, if you begin your brick run following your bike and you’re “tired,” you’re probably experiencing issues due to nutrition, or you’re overheated, or both.

To address nutrition, you would adjust your caloric, fluid, and electrolyte intake, and/or adjust the intensity of your ride for better absorption rates.

To address overheating, you would either employ better methods of cooling—wearing different clothing, splashing yourself, starting your workout earlier when the temperatures are cooler, etc.—or you would learn to adapt to the heat by training in the heat.

To summarize, the way to address nutrition issues and overheating is to . . . address nutrition issues and overheating. A brick workout is not required to do either of these things.

The possible exception would be if you wanted to learn how to run better in the heat. In this case, you would seek to train in the heat, and if you did this following the bike, the run would be occurring later in the day, when it’s probably hotter.

Hard to find running images in Star Wars, but this new Episode 7 R2-series droid looks to be moving at a pretty good clip.

“But so-and-so fast person does bricks. And they’re fast!”

Elite triathletes are not fast runners off the bike because they do bricks. Genetics aside, they are fast runners off the bike because they have trained hard in running.

Why do some professional triathletes do bricks? Why do others choose not to? Without the scientific data to support the efficacy of brick workouts, it’s hard to say.

Okay, so what about anecdotal evidence? Are the pros who do bricks the only ones winning? The answer is no. Some world champions perform brick workouts, some don’t.

Elite ITU athletes racing the Olympic distance would have the most to gain by running as fast as they can off the bike, but even these athletes are split on whether to do bricks. One reason is that they race so often—sometimes every other weekend—they are, in effect, performing bricks every time they race.

And then, there are those athletes like Simon Lessing—multiple world champion at the Olympic distance, but also at the Half Iron and Ironman distance, and now a coach—who are not proponents of brick workouts and feel that running after biking in training only adds to the cumulative stress the athlete is subjected to without quantifiable gains.

By the way, over the last eleven years, we’ve coached Ironman athletes to finishing times of 8:35, 9:42, 9:56, 9:58, and numerous athletes between 10:00 and 10:30 . . . and none of them did brick training to achieve these results. Lest the reader think, “Well, yes, they performed well, but they would have done even better had they done bricks,” it’s important to note that several of these athletes wondered the same thing, and they specifically requested to add bricks to their training to see what would happen. We’re certainly not against working with an athlete to find what works best for them or to try something they are interested in pursuing, so we added bricks to the training plans of those who requested it. The result? There was no measurable improvement in their performances when bricks were added to their training regimen.

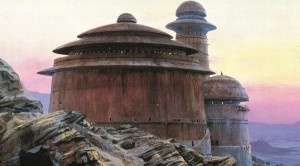

Okay, so the Millennium Falcon has nothing to do with bricks, but this is a flippin’ cool photo! Of course, none of these images have anything remotely to do with bricks, but hey, it’s a long article. Something to keep you reading until the end . . . I hope.

When might bricks be warranted?

- Bike-run repeats. You might do a brick in the form of short, quick, bike-run repeats for the purpose of training the neural system to quickly adapt from bike to run for short course racing.

- “Transition” bricks. A short run following a bike to “test” how well your nutrition worked on a longer bike ride. If you’ve gotten the nutrition right and you’re not overheated, you’ll tick off that thirty-minute run without issue. But even here, the run is not necessary to know this. It’s a confidence builder more than anything.

- Time management. If your schedule is crammed to overflowing , it might be that the only way to fit in that third weekly run is to add it directly after a bike.

- Confidence. As I mentioned above, some athletes just want the peace of mind of knowing they are capable of running after biking. For most, a quick transition brick is all that’s needed. “Yep, it’s been thirty minutes and I’m running like any other run.”

Why might you think twice about performing bricks?

- Run form can be compromised. When you’re fatigued—say you didn’t get your nutrition right on the bike, or you’re overheated after finishing your five-hour ride at 11am in Arizona in July, or you’re not sleeping right because you’re trying to cram in so much training—your run form can suffer. Better to run fresh, to use good form. It will reduce the overall training stress and reduce chances of injury.

- Quality of run workout can degrade. If you’re scheduled for a lactate threshold run, the intensity levels you need to reach for physiological adaptations to occur are extremely high. There’s a better-than-average chance that you won’t reach these high levels of effort if you’ve just come off a three-hour ride, not only because of the fatigue-related issues just discussed, but also due to the mental aspect of having to take yourself to that painful place a threshold run requires. So, it’s not uncommon for that threshold workout to morph into a tempo run or something else entirely.

- Run duration might suffer. With time restraints, when trying to fit in a bike and a run back-to-back, often it’s the run duration that’s effected. If you need a one-hour tempo run, but try to fit it in with a bike before work, you might only have time for a thirty-minute tempo run.

- Cumulative fatigue. This is a biggie, particularly for long-distance athletes, because it can affect the rest of your workouts during the week. Not only might the quality of the run workout that immediately follows the bike be effected, but the cumulative fatigue from brick workouts can inhibit your ability to perform high quality workouts, like interval workouts or tempo workouts, in the days that follow, and as a result, your entire training scheme can soon devolve into a muddle of mediocre workouts.

-

Definite heat stress happening here . . . or maybe an electrolyte imbalance. Whatever it is, it’s not good. Poor Anakin. Quit while you’re ahead! While you still have legs!

Heat stress. For our Arizona athletes who train through the summer, if you run after the bike, you are obviously running later in the day, when it’s hotter. As we all know, this often ends in a survival run rather than the completion of a quality run workout.

- Consistency. If you’re trying to squeeze in a one-hour bike ride before work, it’s difficult enough just to accomplish this and do so consistently. But then to add a run after? Now you’re trying to squeeze in a ninety-minute workout. And for what return? That run could just as easily be accomplished by itself later in the afternoon or the following day with no deleterious effects to the training cycle. In fact, you’ll feel fresher and run with better form and at the correct intensity, as a result.

- Too large a block of time required. Back-to-back workouts require a larger chunk of time to complete, time that we often don’t have due to our busy schedules.

Ideally, if you can keep your runs separate, you can do long-duration runs and higher intensity runs, and do both with better form and at the correct intensity than you could if you make one of your runs part of a brick.

Ultimately, you need to do what is right for you.

This means you have to train not like your next door neighbor, not like the local pro, not like the guy who swims next to you in Masters, but train in the way that makes the most sense for you.

Does this mean you should never do bricks? Not necessarily. Just know that what you may or may not be gaining from doing them, might not be worth the risk of fatigue or injury or the possible negative impact to your other workouts, particularly if you’re focusing on long-distance racing.

The most important thing, really, is focusing on getting your designated swim, bike, and run workouts done consistently. Sounds simple, but for the majority of our athletes with jobs and families and all the rest, this is challenge number one. Do this, and you can still be a triathlete, while doing what’s right for you.

Now, about that tri bike . . .

Wow! Love the Monty Python picture..’It’s only a flesh wound!’ Boy, the older I get the more I realize I’m a student. Yes, I’ve had coaches that have screamed brick or die and some that state for a quality workout stay away from the brick. I gotta admit, I have a problem with getting off the bike and running. My back hurts, I’m a whiner and I cramp a lot! But, I seldom do bricks and if I do they are short with quality, not quantity. When I was young, like yoda, I never did a brick in my life. I raced very well. Also, I really don’t believe in muscle memory or neuro transmitter motions. So, I only do bricks if a race dictates something different. Take a race with a huge hill off the bike, might be a good idea to practice this. But, I agree, a quality workout is simply that, a(1) quality workout. 2 workouts in my eyes, makes for two mediocre workouts, which in turn makes for mediocracy. Once again, just my two cents.

Well said and written Ann and Bill..

Appreciate the info as I enter my first year of Ironman Training.. Have heard those suggest brick etc.. I get it if your new to sport with a short race .. Btw can’t wait to read your book being published !!

Great article Anne – really fun and informative read. My feeling is, as someone who trains regularly but races infrequently, I get something out of running off the bike (I just need a couple miles, enough to get past the discomfort and into a running rhythm). Maybe it’s more mental, but I think it helps me to replicate that race sensation of running on dead legs. Perhaps if I raced more I wouldn’t feel like I need them, but for me, I like doing short bricks if I have time.